The History of Skarhult

By the banks of Bråån, where Skarhult Castle is situated today, laid the medieval village of Skarhult. Livestock was the principal industry and the village’s marshy meadows gave ample pasturage for the cattle. Not until much later would a renaissance castle be built on the site – a stronghold which still stands there today.

On a stone tablet over the east gate to the castle it is written:

"Anno D:ni MDLXII lod Sten Skarolt som kallis Rosenspar bygge thette hus,

Gud unde hannom med hostru oc born saa d bygge oc bo, attij til samen maa hafue then evig roo"

The inscription states that Steen Rosensparre built “thette hus” (this house), or more specifically, the east wing in 1562.

Stone tablet above the east entrance.

The family Rosensparre

The first person we know of who belonged to the family which would take the name Skarhult, was Johannes Nielsen. He might have even lived in the building whose mortar remains in the cellar of today’s castle. His office was later held by several of his descendants, which proves the family’s importance. The family called themselves Rosensparre after its coat of arms – three red roses on a silver chevron against a blue background – and they came to rule over Skarhult for several centuries.

Steen Rosensparre died in the battle between Sweden and Denmark at Axtorna hed in 1565. His widow, the powerful and intelligent Mette Rosenkrantz of Vallö, remarried a couple of years later to Peder Oxe of Gisselfeldt. Peder Oxe was the owner of a large amount of properties as well as Ravnsborg County. As Steward of the Realm, Peder managed Denmark’s finances for a long time. Amongst other things, he created the customs over the Sound (Öresund), an important source of income for the country. When Peder Oxe died in 1575, his wife Mette Rosenkrantz inherited his large fortune. Combined with her own fortune, she became the richest woman in Denmark.

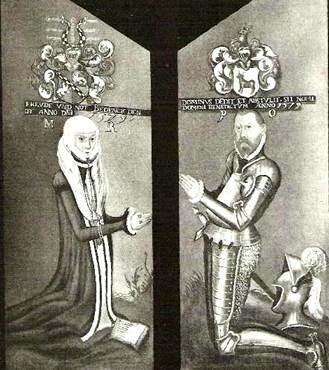

For a long time, it was believed that Mette Rosenkrantz was buried in Skarhult Church, after her death at Skarhult in 1588. In the church, Mette Rosenkrantz had the arches decorated with paintings portraying scenes from the life of Jesus. She has also been depicted together with her husband on a grand tombstone within the church as well.

Mette Rosenkrantz and Peder Oxe in prayer.

However, the architect Brunius stated that only one coffin was found during an excavation – the coffin of Steen Rosensparre. It was then discovered that Mette Rosenkrantz had been buried next to her second husband Peder Oxe in the church Vor Frue Kirke in Copenhagen.

The son of Mette and Steen, cabinet minister Oluf Steensen Rosensparre, inherited Skarhult and ruled it for 36 years. It is probable that he is the one to enlarge the castle by building the west wing, and therefore continuing the work his parents started. When Oluf died in 1624, the family Rosensparre was left without a male heir.

Oluf Steensen Rosensparre’s daughter Birgitte, lady’s-maid to the queen, married the wealthy nobleman Corfitz Eriksen Ruud of Sandholt. They bought the part of Skarhult that belonged to Birgitte’s sister and became therefore sole owners of the estate. At Frederiksborg Castle in Denmark, there hangs today an interesting painting from the 1630’s by Remmert Piettersz called ”Dansen med Rud´erne.”

“Dansen med Rud’erne” from ca. 1630. Probably painted by Remmert Piettersz.

This painting shows an elderly Corfitz Ruud and his wife Birgitte Rosensparre gazing at their three daughters, dancing with their partners to music by four trumpeters. The dancing couple to the left is Birgitte and Corfitz’s eldest daughter Mette Corfitzdatter and her husband Niels Trolle of Trolleholm. Mette would later inherit Skarhult. When their son Corfitz Trolle came of age in 1649, he inherited Skarhult from his mother. Corfitz Trolle became the last of Skarhult’s Danish-Scanian owners.

Beata von Königsmarck

When Scania became Swedish, in 1658, the country’s nobility succeeded to lay their hands on the province’s finest estates.

According to previous written history, Count Pontus Fredrik De la Gardie was the one who bought Skarhult from Corfitz Trolle. Pontus Fredrik De la Gardie was the son of Ebba Brahe and brother of Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie. His career as cabinet minister, war councillor, and President of Dorpat’s Court of Appeal, brought him far away from Scania, hence it was unlikely that he had the opportunity to visit Skarhult very often.

However, new research shows that it was not Pontus Fredrik De la Gardie who bought Skarhult in 1663, but his wife Beata Elisabeth von Königsmarck who purchased it with her own money. Since married women were minor, she did not appear in the list of owners until the death of her husband in 1692.

Beata Elisabeth von Königsmarck. Oil on canvas by Hendrick Munnichhoven, 1654.

Beata von Königsmarck was the daughter of field marshal Hans Christoffer von Königsmarck. She repaired the cowshed after a fire in 1676 and came to posses Skarhult for 62 years. She survived not only all of her four daughters, but also all of her grandchildren, save one. When she died in 1723, the inheritor of Skarhult was her two-year-old great grandson, Erik Brahe.

Brahe and Piper

Erik Brahe received his military training at “Norra Skånska Kavalleriregementet” where he advanced to a major. During this time he temporarily stayed at Skarhult. Most of his time was spent at his many estates in northern and central Sweden. He became colonel over the mounted lifeguard regiment in 1752, and served as field marshal for parliament in 1751-52. Erik Brahe was one of Adolf Fredrik’s confidantes; he belonged to the court party where he got involved in their plans to execute a coup d’état. The coup, however, was stopped prematurely. Regardless of the fact that there was no evidence of Erik Brahe’s participation in the coup, he got sentenced to death and was beheaded in 1756. That same year, four of his children died. His son, who came to be the formal inheritor to Skarhult, was born a couple of months after his father’s execution.

Erik Brahe, one of King Adolf Fredrik’s confidantes.

Stina Piper, grandchild to the powerful Christina Piper – one of Sweden’s principal entrepreneurs through history.

For a long time to come, the estate was taken care of by the inspector and cornet Olof Wallstedt. New research shows that Erik Brahe’s wife Stina Piper received Skarhult as a wedding gift in 1754, and that she ran it until she remarried with Ulrik Scheffer in 1773.

Their son, Count Magnus Fredrik Brahe, became one of King Gustav III’s favourites. In 1778, he was the one to carry the crown prince Gustav IV Adolf at his christening, and he was the first holder of the dignity “a man of the realm”. He later ended up in opposition with King Gustav III, but they reconciled at the kings deathbed. In addition to managing his large estates Skarhult, Rydboholm, Skokloster, and Salsta, Magnus Brahe was also a field marshal and a chancellor at Uppsala University. He was held in high esteem for his honesty and humility, and then became a confidante of King Karl XIV Johan. He rarely visited Skarhult and none of his eleven children were born there.

The family von Schwerin

Magnus Brahe’s son, who inherited his farthers name, became Karl XIV Johan’s closest friend and advisor. He received much influence and people often discussed “Braheväldet” (the Brahe empire). When Magnus Brahe the elder died in 1826, the heirs sold Skarhult to the King. However, the castle was in a poor condition due to its previous lack of inhabitancy. After the death of Karl XIV Johan in 1844, Skarhult was sold to the cavalry captain Baron Carl Johan Gustav Adolf Julius von Schwerin (also known as Jules). The family von Schwerin originates from the 12th century’s Pomerania and came to Sweden during the 16th century. Jules continued the restoration project of Skarhult after the suggestions of architect Brunius. Finally, after centuries of sleep, the castle became inhabited once again and an English park was constructed. In 1849, Jules von Schwerin married Ingeborg Rosencrantz and together they had five children. Three of the siblings remained unmarried and lived at Skarhult their entire lives.

King Karl XIV Johan, sovereign over Ponte Corvo and owner of Skarhult.

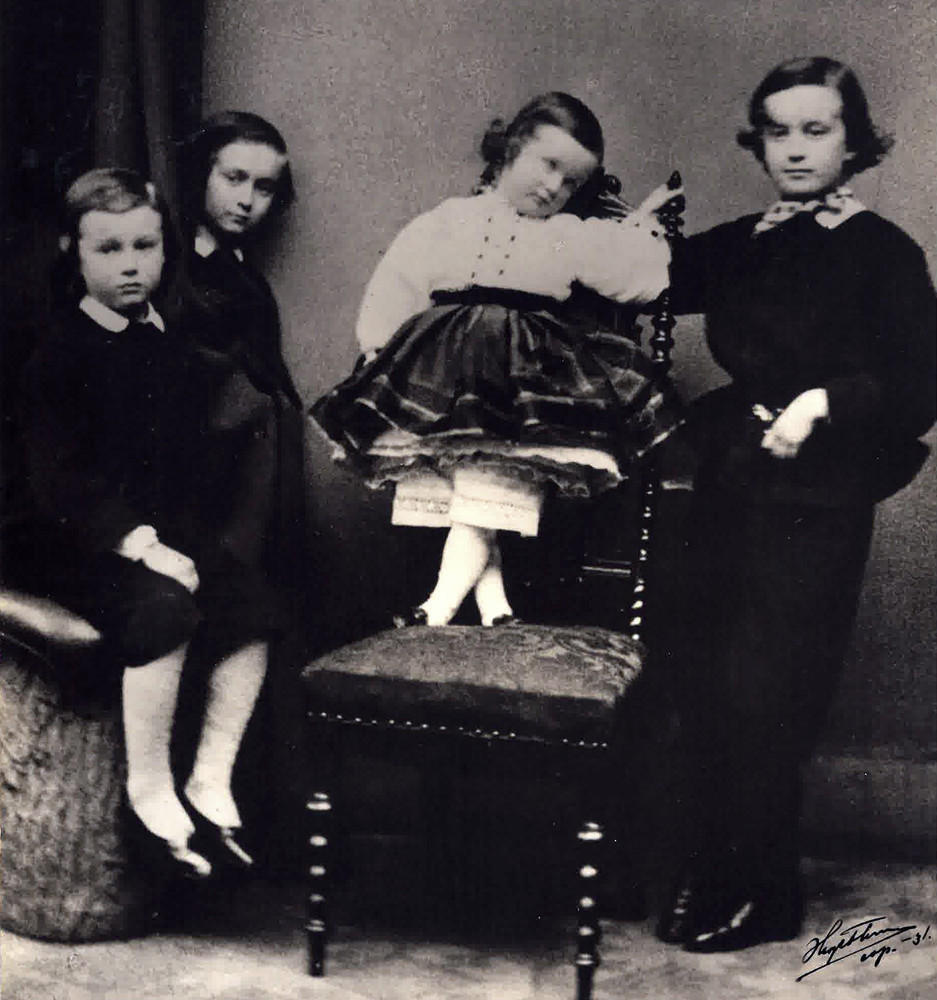

The children of Ingeborg and Jules von Schwerin. From left to right: Bogislaus, Hans Hugold, Elysabeth, and Werner Gottlob. The youngest daughter Richardis was born first in 1867. The photo is taken circa 1860.

Werner von Schwerin, who took over the castle in 1880, continued the restoration of both the castle and the park. It has been told of how Werner, in an attempt to better the luck in hunting, had wild rabbits imported and released on the grounds. However, the rabbits propagated faster than expected and overflowing amounts of them soon plagued the neighbourhood. This led to annoyed neighbours suggesting that it should be written “Grateful rabbits erected this monument” on the baron’s gravestone.

In 1922, Werner’s nephew, Baron Hans Hugold Julius von Schwerin, became owner of Skarhult. During this time, Skarhult was modernised both in agricultural and social aspect. Hans Hugold von Schwerin is known as the author of many books about Scanian castles and their history.

Hans Hugold’s wife, Margaretha von Schwerin (born Uddenberg), opened Skarhult’s School of Domestic Science in 1944.

Skarhult’s School of Domestic Science

The School taught hundreds of girls to run and manage larger households. In the information brochure from 1944, it is written:

"Young girls of our time often lack the understanding and experience which are required to grasp the importance of their duties as housewives."

Many girls sought themselves to Skarhult’s School of Domestic Science to learn how to become ideal housewives.

The school offered its students either a course for eight months split into two semesters, or a shorter course for six weeks over the summer. The education consisted of cooking, baking, washing, home help, childcare, tailoring, hostess-ship, and home nursing. The school was run until Hans’ death in 1957. Margaretha and Hans Hugold von Schwerin’s son Werner took over the estate in 1957 and he later married the Danish lady-in-waiting Lykke Horneman in 1968. The couple had four children: Martina, Carl Johan, Sofia, and Beatrice. Werner was chairman of the Frosta County District Heritage Association, involved in the Rotary Club, the Freemasons, and the Pimpinella Order. He was also a councillor for Moderaterna (the Conservatives) in Eslöv’s local government during the 1970’s and 1980’s.

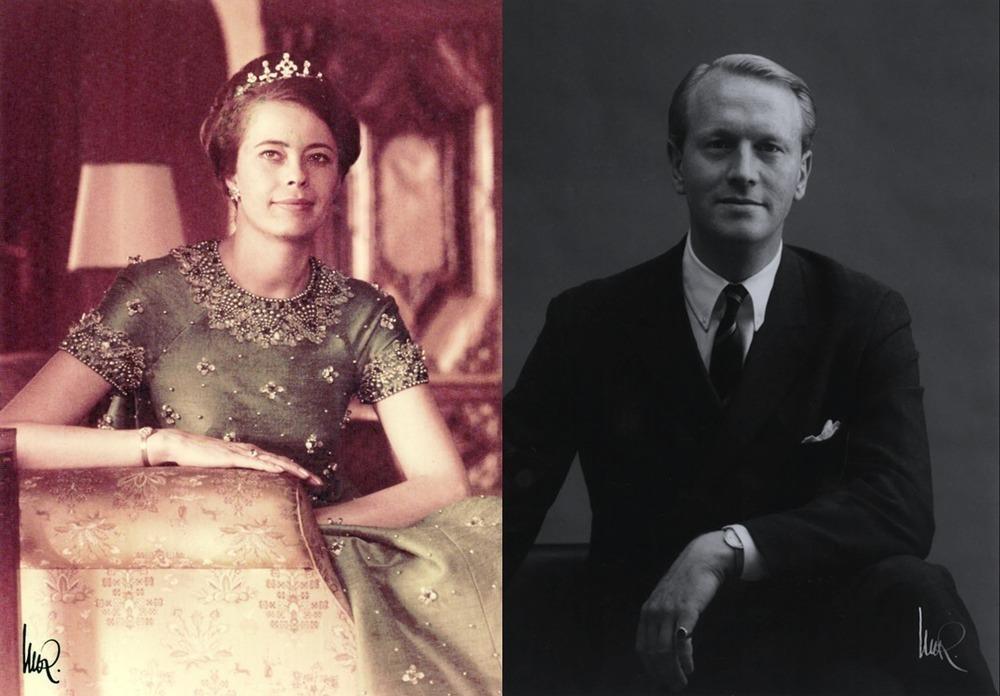

Lykke and Werner von Schwerin in 1968; the year they married.

Alexandra and Carl Johan von Schwerin.

Skarhult today

In 1988, the son Carl Johan von Schwerin inherited Skarhult.

Carl Johan realised that the estate needed to extend its sources of income and become less dependent on oil. The traditional farm was therefore complemented with two wind turbines in 1999. Two more were built in 2001, and another four in 2009.

Both the farm and the residential houses are now provided with local and green energy from the surrounding fields.

Today, Skarhult is run by Carl Johan von Schwerin and his wife Alexandra.

The couple is working to develop both life and activity on the farm, the estate, and its surroundings. The properties have been renovated and new tenants move to Skarhult every year. They also chose to open the castle for the public in 2014 with the exhibition Power in Disguise.

The architecture of Skarhult

Skarhult is one of Sweden’s best preserved castles from the renaissance era, built under leadership of the chatelaine Mette Rosenkrantz in the 1560’s. It was later restored to its former glory by architect Carl Georg Brunius in the 1850’s.

From the Middle Ages to Renaissance

The oldest part of the castle is the south wing, closest to the park and river. It previously used to be a two-story house and parts of the older house’s wall are visible from the courtyard. They are easy to distinguish due to the darker bricks built in a Flemish bond contrasting themselves to the lighter bricks, from later renaissance constructions. The older house was most likely built in the early 16th century and resembles the long and narrow Glimmingehus, outside Simrishamn. Remains of even older buildings are preserved beneath the south wing. The walls in the west cellar are more than two meters thick, almost as thick as the walls found in the east section of the castle. These walls suggest that there had previously been an almost quadratic building (possibly from the 14th century) whose upper parts were demolished when the south wing was built.

The castle’s second oldest part is the east wing. Above its entrance is a stone tablet that states how Steen Rosensparre built the house in 1562. Above the inscription there is a relief of the Holy Trinity flanked by the Rosensparre and Rosenkrantz’ coat of arms. The east wing is distinguished with decorative adornments; intact renaissance decorations are very rare in Scanian castles. August Hahr, who has analysed Skarhult’s architectural history in the book Skånska borgar, also presumes that the east wing used to have had traditional stepped gables. The castle’s gables are currently a Dutch style, with volutes and cornices of sandstone; an effect which did not spread to Denmark until the 1580’s.

Skarhult Castle seen from the north in February 2013. The east wing is to the left of the picture, the south wing in the middle, and the west wing to the right.

From 1581-86, the widowed Mette Rosenkrantz had a mighty castle built at her family estate Vallö. The stonemason is unidentified but is usually named Eiler Grubbe’s sculptor. It is known that he created the first larger renaissance sculpture in Scania, namely the laymen’s altar in Lund’s Cathedral in 1577. The mannerist mantelpiece of sandstone at Skarhult is believed to be the work of that same nameless artist. It is therefore believed that the renaissance decorations at Skarhult were ordered in the 1550’s by Mette Rosenkrantz, and not before. The six-story high tower was possibly added during the same time, together with the fireplace, which was later moved to the south wing.

A sand stone mascaron of a lion on one of the east wing’s turrets.

The decorations on the façade are somewhat mysterious. They are lacking any direct context to the Dutch architecture of that time. Instead, they testify of a style used in older times.

The castle’s newest segment is the west wing. It was built in the late 16th century, probably by the son of Steen Rosensparre, Oluf Steensen Rosensparre. Although the west wing surpassed the south wing, the old gable in the south wing is preserved. Today, that gable of late medieval style can be seen as the inner wall of one of the west wing’s southern bedrooms. Since the west wing was built, the castle’s shapes have remained roughly the same. The intention was to eventually build a north wing to encircle the courtyard, however, the courtyard har remained open.

In wartime

In 1676, during King Karl XI’s Scanian War, the castle’s cowshed burnt down in a fire, though the lower part of its gate tower remained intact. Burman-Fischer’s work of prospect from the 1680’s shows an overview over the estate. The left side of the poster shows the still roofless cowshed, and on the south wing is a scepter, which is now gone, can be seen.

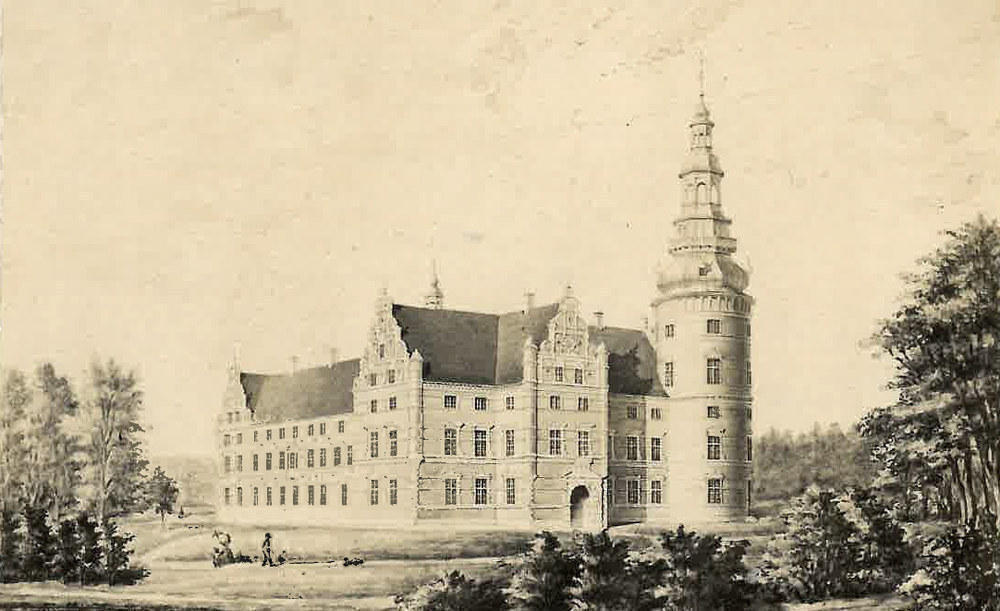

Skarhult, ca. 1680, from Buhrman-Fischers work of prospectus. The cowshed lacks a roof due to war ravages.

Burman-Fischer’s poster was first and foremost meant to show the buildings’ appearance rather than portraying the nature. However, the estate was at this time surrounded by beautiful woods and great fields where a large amount of hay was harvested annually. While looking at the poster, one can imagine the village just east of the cowshed.

Lorents Gillberg wrote in 1765 that the estate was surrounded by a massive ring-wall, 5 ells high and equipped with apertures, with a wide trench outside. A drawing by Ulrik Thersner shows that the wall was still standing in 1817. Unlike Burman-Fischer, Thersner uses the building more as an excuse for drawing the nature surrounding it and the castle is almost invisible among the greenery.

In the 1820’s, the windows on the eastern exterior were enlarged, which destroyed the moldings.

The east wing of Skarhult. Note how Bruinus’ windows are placed inside larger and older frames.

Carl Georg Brunius

In the 1840’s, the castle had been uninhabited for nearly a century and was therefore in grave need of restoration. Consequently, a renovation of the castle’s exterior was commenced in 1843 by orders from King Karl XIV Johan.

This assignment was led by Professor C.G. Brunius. At the same time, the windows on the eastern façade were restored to its previous size. Furthermore, the park, which can be seen today, was also constructed.

Brunius’ suggestion for reconstruction, however, this plan was never put to practice.

Autumn view over the river Bråån and Skarhult’s English park.

In the book Skånska herrgårdar (Scanian manors) from 1854, Gustaf Ljungren described the village in the following way:

"The thatched huts, shaded by the thickly wooded elm-trees, anxiously gather around the castle, as if seeking protection against an expected enemy."

The castle was originally built to withstand resistance against enemies – a precaution that proved itself useful during the Dano-Swedish wars. Traces of apertures can be found yet today in the base of the roof, both in the south and west wing, as well as gaps for canons in the great tower. The defense was supplemented with moats around the today demolished wall and reached the stone-built cowshed, whose gate tower offered defense towards the east.

Aerial photograph of Skarhult, probably from the summer of 1940. The hedges to the north were probably so high that they created arbours.